Insights by Edinburgh-based researcher of tourism, Stephen Harwood.

“When tourism emerges, I hope that it will be different for the reasons that will become apparent with my unfolding story about my many years of research into tourism and specifically Edinburgh’s tourism.”

Tourism in Scotland & Edinburgh – insights from nearly two decades of research

Dr Stephen Harwood

Its June 2020 and the world has come to a standstill with covid19. Tourism is in enforced hibernation with international travel almost non-existent. Lockdown has seriously restricted domestic travel.

When tourism emerges, I hope that it will be different for reasons that will become apparent with my unfolding story about my many years of research into tourism and specifically Edinburgh’s tourism.

Tourism is a resilient industry, but it may be a while before tourism reaches the volumes previously experienced with nervousness and restrictions inhibiting growth. Moreover, increasing calls[i] for sustainable tourism which address not only environmental issues (e.g. plastics, energy), but also affected communities may result in lasting changes in the values underpinning being ‘in’ tourism. The mantra that ‘tourism is everyone’s business’ needs to be displaced by a new mantra – ‘tourism is everyone’s concern’. This concern is about the damage that has been done to both environment and communities and how to prevent this in future. However, this is not new thinking. Sustainable tourism guidelines[ii] for policy makers have existed since 2005, produced by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Tourism Organisation (WTO). Nevertheless, it is open to question about who has paid any attention to them, particularly on issues such as climate change, over-tourism & community displacement.

Sustainable tourism is an important issue which has dominated my more recent thoughts about tourism. It is a very different industry to that which existed fifty years ago in Scotland and specifically Edinburgh. Then, there was greater fusion between community and the many individual small independent tourism businesses. Today, tourism is big business with many of the smaller independent businesses (e.g. guest houses) faded into oblivion. One recent phenomenon is AirBnB with its transformative effect upon the rented accommodation market. Irrespective, tourism is a complex industry, which is reflected in the need for such measures as Tourism Satellite Accounts[iii]. Thus, it is not possible to go into all the issues relating to tourism. That would take time and many words. Instead, I would like to share my own research.

My earliest memories of tourism was as a very small kid when my mother ran a B&B in the top flat of 2 Merchiston Place. Then the family moved to 59 Linkfield Road, Musselburgh which led to my immersion into an industry from which there has been no escape – many older people in Edinburgh will remember what this family home became. It was also where Billy Connolly had his first solo gig. Whatever, tourism is in my blood and has become a love-hate relationship like no other.

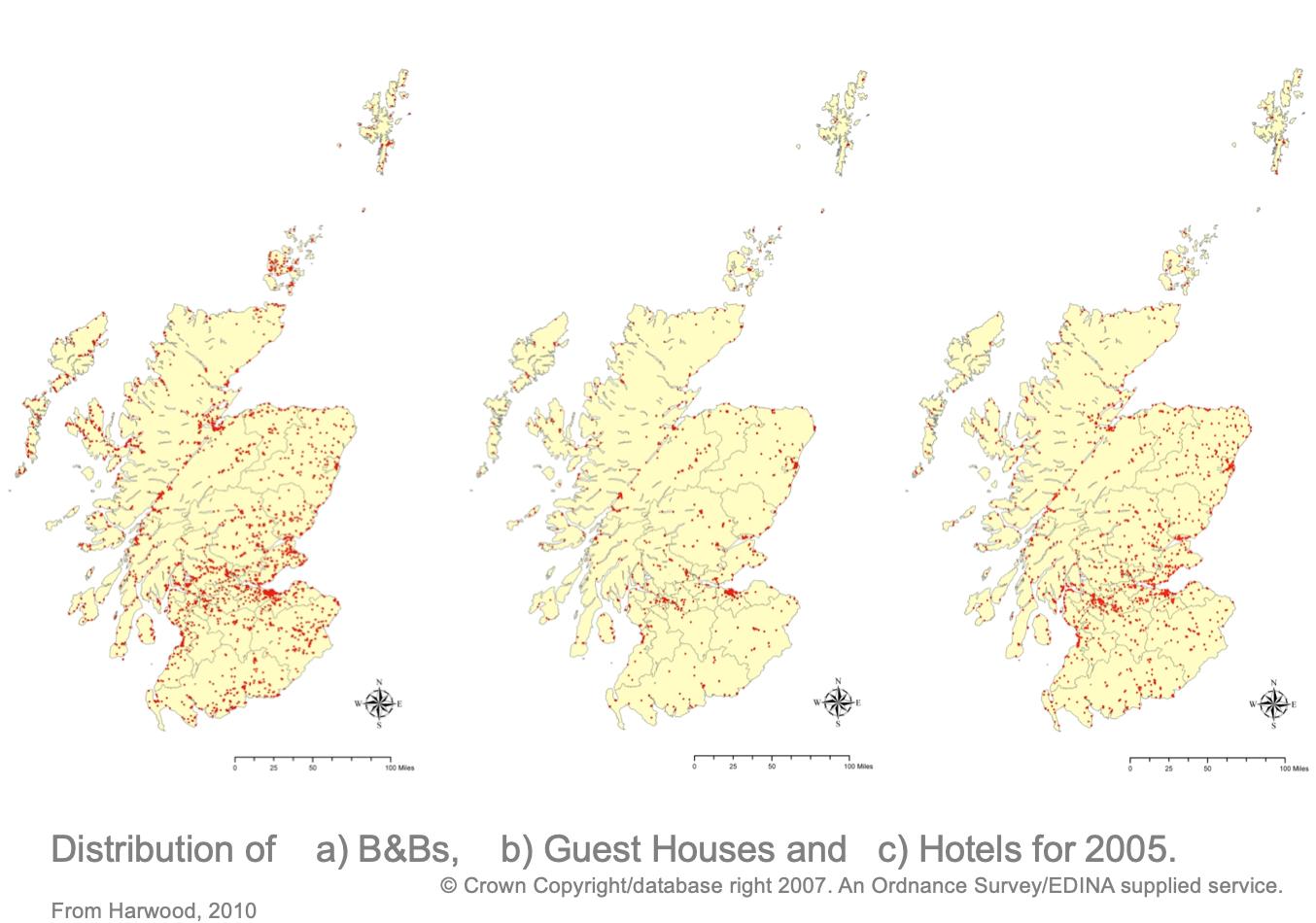

My academic interest in tourism started in 2003 examining the online practices of Scottish serviced accommodation providers. This revealed how the online is domesticated (2011[iv]), the metaphor of domestication capturing the manner in which we tame online technologies. Whilst my initial interest was technology, my tourism blood got the better of me. Aside from a detailed study of online practices, it allowed me to develop an understanding of the composition of serviced accommodation in Scotland (2007[v]) which offered the opportunity for me to map out the positions of all the sites (figure 1). It also prompted a discussion about the importance of location (2012[vi]) for attracting the visitor, whether this a physical location, but also location online and how found. One conspicuous aspect of this was insignificant presence of hotel chains at that time. The value of this profile is that it provides a baseline against which subsequent serviced accommodation developments can be evaluated such as the prominence of hotel chains[vii] in Edinburgh. Moreover, since online practices involved online intermediaries, which included VisitScotland, nee Scottish Tourist Board (STB), attention was given to how the STB developed over time (2008[viii]). At the time of writing this, the controversy erupted about VisitScotland’s online platform and its charges, with a petition to the Scottish Parliament, to which I was invited to give evidence (2007[ix]).

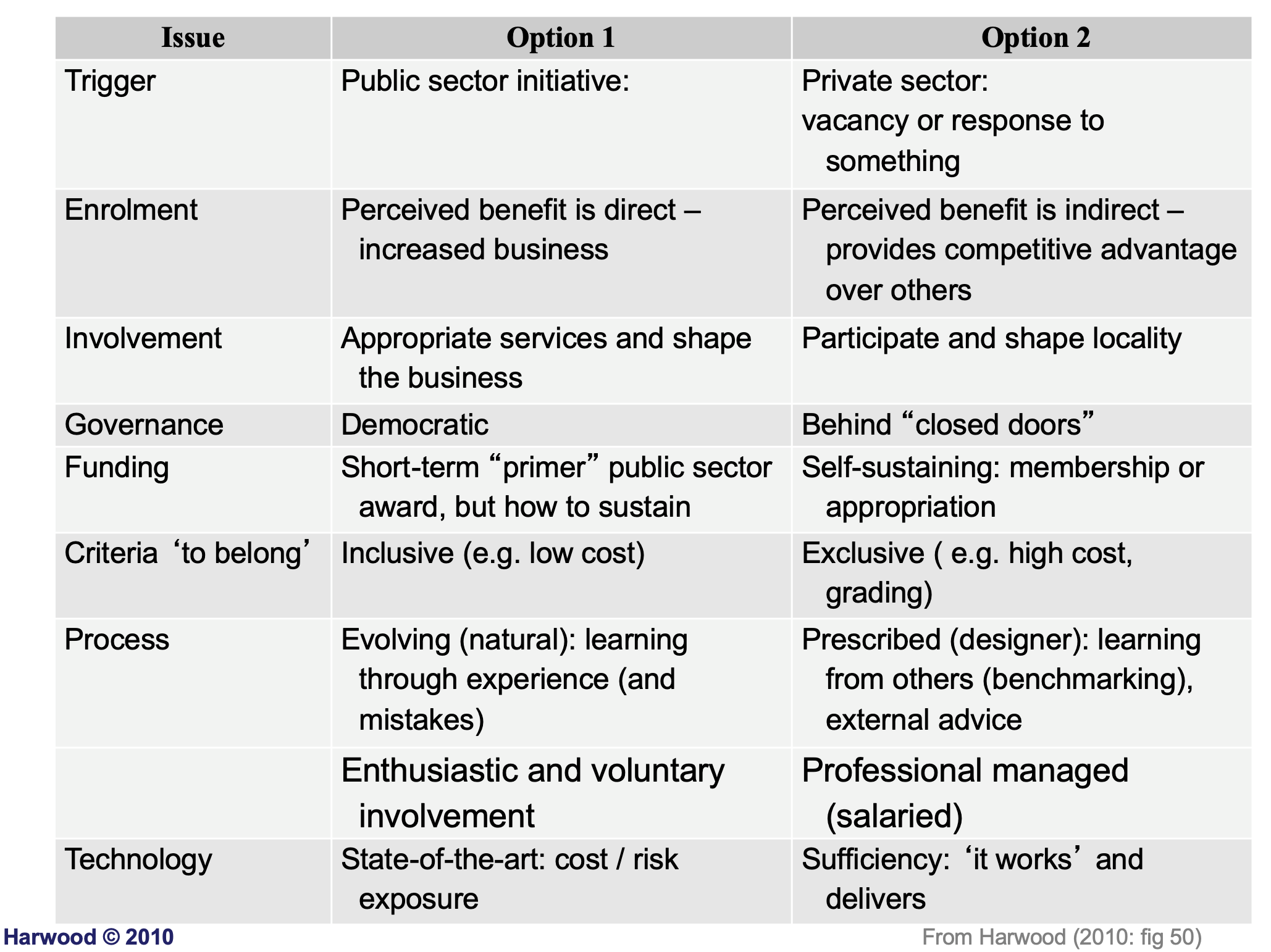

One of the unexpected aspects of my study into online practices was my discovery of local tourism groups scattered around Scotland. Mull had perhaps one of the earliest groups (1977). However, the dissolution of the membership based Area Tourist Boards (ATBs) on the 1st April, 2005 (2009[x]) triggered the emergence of new groups (e.g. The Orkney Tourism Group and the Shetland Tourism Association). I studied ten locations in detail, mainly island locations due to their bounded spatiality, but also Dumfries & Galloway and Edinburgh. Each group was unique with a different operating model, their analysis allowing the critical elements to be identified (figure 2). Edinburgh was conspicuous by its fragmentation with limited co-ordinated activity. Edinburgh Tourism Action Group (ETAG: formed in 2000) was the dominant organisation with emphasis upon destination development, whilst Destination Edinburgh Marketing Alliance (DEMA) was formed in 2009 to take responsibility for marketing Edinburgh, this transforming in 2011 into Marketing Edinburgh.

What was emerging was a deep appreciation of the interplay between policy and practice and the role of local groups, which I wrote up in a holistic analysis of the structure of Scottish tourism (2009[xi]). It explained the disconnect arising from the abolish of ATBs, which had led to an interest into how Scottish tourism was viewed strategically and how this managed, reflecting my industrial background in strategy development. Six national strategies emerged between 1975 and 2012, with the ill-fated 2006 strategy being the topic of two parliamentary reviews. Whilst the earlier strategies were public sector led, what distinguished the 2012 strategy was that it was industry led under the leadership of the Scottish Tourism Forum (STF) then the Scottish Tourism Alliance (STA), which replaced the STF in 2012. This strategy emerged after an admirable process of consultation with all parts of the industry. Moreover, the STA, through its membership, restored the integration of the diverse stakeholders, scattered with the demise of the ATBs.

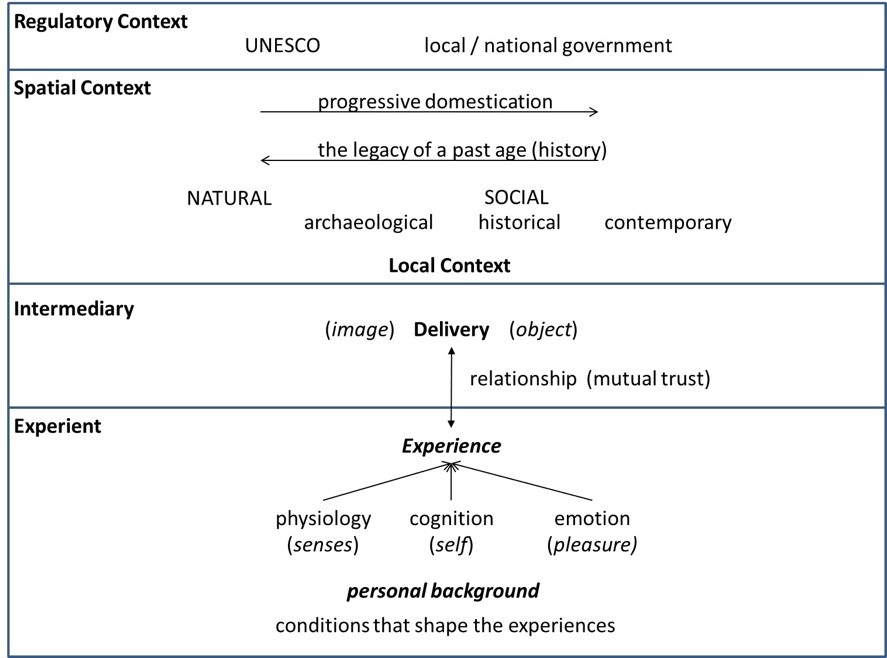

However, whilst I was interested in the industry’s dynamics, inspired by my long association with organisational cybernetics, I was being seduced by a word that constantly appeared in my reading of tourism materials. Authenticity – a word which appeared to be extensively used to enhance the attractiveness of a destination, but, what does it mean? I moved into unfamiliar territory and decided to explore this provocative word. I developed the argument that if I was to find authenticity then I would find it close at hand in the Royal Mile, which has led me to focus in upon the city of my childhood. Early in 2011, enrolling a colleague, we conducted an extensive review of the literatures on authenticity and carried out five audits of the Royal Mile, each audit conducted in a specific week in June. Three of the audits have been published as reports for the years 2011[xii], 2012[xiii] and 2013[xiv]. Even over this two year period the changes were marked, exposing the shift from community to tourist. In the search for authenticity, the Royal Mile revealed it its rich habitat. However, as explored in a paper (2012[xv]) and presented at NA:WH [0729][xvi] [12-15th March 2013], the recognition of authenticity was elusive and complex, with an attempt to capture its dimension in figure 3. This is explained in the recording[xvii] of my presentation, which, incidentally, was introduced by Jukka Jokilehto, an influential author on authenticy with a long association with the international cultural conservation organisation ICCROM! Whilst authenticity might be difficult to define, if the meaning or significance is stripped out of whatever we are referring to, the more inauthentic it becomes – culminating in total disregard of the meaning or significance of whatever, in the pursuit of making a ‘quick buck’. This has implications for those who are the guardians of the space or ‘place’ and whether they ensure there is anything to pass on to future generation that has meaning and significance for this place.

I am sad to say that there is more to my research that is un-published due to time. My reports of my audits of 2014 and 2015 were never completed due to other demands, but I think three years sufficiently demonstrates the change. Further, there is other material. For example, I reconstructed the Royal Mile for the years 1774, 1814, 1864, 1914 and 1964. This offered a fascinating insight into its changes, with all periods characterised by a strong community presence. It is all interesting, but at the end of the day, I do ask the question – so what?

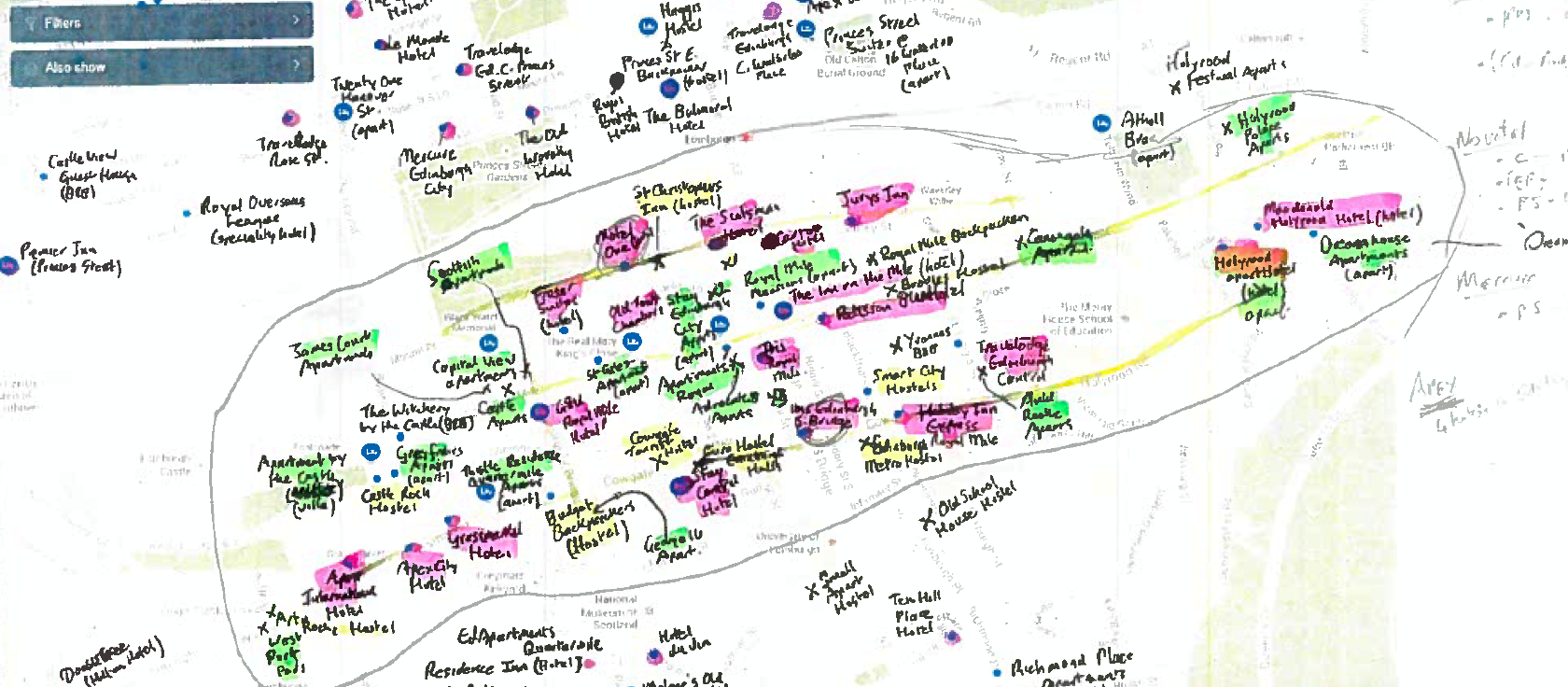

Over the last seven years, I am perceiving Edinburgh to be changing into something unrecognisable and unpleasant, especially around August with its noise, overcrowding and cost. Has Edinburgh commodified itself and become a market, selling whatever there is to sell in order to make ‘quick buck’?. I have observed the explosive growth of city centre accommodation to service visitors as illustrated in the crude mapping in 2014 of hotels, hostels and serviced apartment in the vicinity of the Royal Mile (figure 4). How much of it was there in 2005? How much has arisen since? I have also observed the growth in visitor numbers, informed by VisitBritain’s statistics[xviii] about international visitors. Edinburgh in August. Indeed, one of the questions that I have repeatedly asked in meetings over the years is ‘who is the visitor?’. No-one seems to be able to answer my question. Is this not an important question? Further, what is the impact of these rising numbers upon the community, especially those who live in Edinburgh but are not part of the tourism machinery? The public debate about the Royal High School on Calton Hill has surfaced the growing tensions between community and tourism, becoming more acute with the more recent rise of AirBnB and the lack of affordable housing to rent. Add to this, issues such as climate change, plastics pollution, mobility, poverty and inclusion.

I am sure that there will be some who do not perceive there is a problem and have an opposing view to mine. In response, when it becomes a challenge for a long term resident of Edinburgh to rent affordable accommodation in Edinburgh, then perhaps this is symptomatic of a serious deep-rooted social problem that needs a major disruption to bring about a rethinking and change. Perhaps covid19 is that disruption.

Unpleasant as it is to observe, tourism is going through the same pains as other Scottish industries have experienced in the past – textiles, ship-building, steel, mining, electronics… I, along with many others, was caught in the 1986 global collapse of oil exploration. It IS painful. However, it is an opportunity for rethinking the role of tourism in Edinburgh. Whilst this crisis calls for collaboration with those who can support, it also calls for re-discovery and re-invention. It calls for perseverance. I suggest that as part of this re-discovery and re-invention that attention is given to the community and better integration of community into local planning decisions. I suggest deeper engagement with the #SDGs. I suggest a move to sustainable tourism as defined by the aforementioned UNEP/WTO guidelines[xix] on sustainable tourism.

Whatever, tomorrow is surely to be different.

TOURISM RELATED REFERENCES:

| Journal papers: | |

| 2011 | The Domestication of Online Technologies by Smaller Businesses and the ‘busy day’. Information and Organization, 21(2), 84-106. EDITOR’S CHOICE, June 2015 |

| 2009 | The changing structural dynamics of the Scottish tourism industry examined using Stafford Beer’s VSM. Systemic Practice and Action Research, (special issue: Action Research in Organisational Cybernetics), 22(4), 313-334. [ABS2] |

| Conferences: | |

| June 2013 | The Uses and Abuses of Heritage: Past and Place-Making in Scotland. WORKSHOP: Friday, 21st June 2013. |

| Mar, 2013 | Framing authenticity in Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. na:wh [0728] Conference on World Heritage, 15th Mar, 2013 University of Edinburgh. link |

| Working Papers: | |

| Aug, 2013 | An Audit of a UNESCO World Heritage site – the Royal Mile, Edinburgh: a preliminary search for authenticity – Two years later. Working Paper, Series: 13.01, Business School, University of Edinburgh [ISBN: 978-1-906816-09-4]. |

| Oct, 2012 | The Performativity Turn in Tourism. Co-authored with Dahlia El-Manstrly. Working Paper, Series: 12.05, Business School, University of Edinburgh [ISBN: 978-1-906816-08-7]. |

| Aug, 2012 | ‘Authenticity’: a familiar word but what are the implications for a destination if it is a popular tourism destination as well as a UNESCO World Heritage site? Co-authored with Dahlia El-Manstrly. Working Paper, Series: 12.04, Business School, University of Edinburgh [ISBN: 978-1-906816-07-0]. |

| Jul, 2012 | An Audit of a UNESCO World Heritage site – the Royal Mile, Edinburgh: a preliminary search for authenticity – One year later. Co-authored with Dahlia El-Manstrly, Business School, University of Edinburgh. Working Paper, Series: 12.03, Business School, University of Edinburgh [ISBN: 978-1-906816-06-3] |

| May, 2012 | An Audit of a UNESCO World Heritage site – the Royal Mile, Edinburgh: a preliminary search for authenticity. Co-authored with Dahlia El-Manstrly. Working Paper, Series: 12.02, Business School, University of Edinburgh [ISBN: 978-1-906816-18-6]. |

| May, 2012 | ‘From the spatial to the digital domain’ : a need for hotelier reconfiguration? Co-authored with Dahlia El-Manstrly. Working Paper, Series: 12.01, Business School, University of Edinburgh [ISBN: 978-1-906816-17-9]. |

| Jan, 2009 | A Difference Of Interpretation? A content analysis of the ‘Evidence’ of the Scottish Area Tourism Board Review, 2002-2004. Working Paper, Series: 09.01, Business School, University of Edinburgh. |

| Nov, 2008 | A Narrative About Institutional Developments In Scottish Tourism 1969-2008. Working Paper, Series: 08.04, Business School, University of Edinburgh. |

| Sep, 2007 | A Quantitative Analysis of Serviced Accommodation Providers in Scotland over the Period 2003 to 2007. Working Paper, Series: 07.01, Business School, University of Edinburgh. |

PhD Thesis

| 2010 | The Domestication of ICTs – the case of the online practices of Scottish serviced accommodation providers. Business School, University of Edinburgh. |

Other:

| Aug. 2013 | Cashmere shops ‘make Mile bland’, GLASGOW HERALD, 21st Aug, 2013 |

| Aug. 2013 | Bland’ Royal Mile full of cashmere shop clones, EDINBURGH EVENING NEWS, 20th Aug, 2013 |

| May, 2007 | submission of evidence (by invitation) to Public Petitions Committee, Scottish Parliament (PETITION: National Tourism Website (Public Ownership) (PE1015) |

This research has been acknowledged by The Cockburn Association: Euan Leitch: Royal Mile shouldn’t just be for tourists, 27th Feb. 2013.

Planning Democracy, drawing upon this research, highlighted the importance of the ‘local business’ in contrast to the ‘foreign investor’ for local economic development:Economic Benefit? Maybe, but Where, and for Whom? A Closer Look at Edinburgh City Center’s Hotel Boom, 31st March 2014.

[i] https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development

[ii] https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284408214

[iii] https://www.unwto.org/statistics

[iv] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471772711000121

[v] https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/a-quantitative-analysis-of-serviced-accommodation-providers-in-scotland-over-the-period-2003-to-2007%282e7b4bfe-db89-46e3-be6e-a620679c03df%29.html

[vi] https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/from-the-spatial-to-the-digital-domain%28b9aff1e5-3b10-47c6-b82d-8a6989b6fa2b%29.html

[vii] https://www.edinburgh.gov.uk/downloads/file/27445/hotel-development-schedule-2019#page=1&zoom=auto,-14,-28

[viii] https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/a-narrative-about-institutional-developments-in-scottish-tourism-19692008%289225da36-9360-4177-981c-c9775b37fd17%29.html

[ix] https://archive.parliament.scot/s3/committees/petitions/papers-07/pup07-03-current2.pdf

[x] https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/a-difference-of-interpretation-a-content-analysis-of-the-evidence-of-the-scottish-area-tourism-board-review-20022004%28f4978fa2-410a-4e5f-9241-d2eb379b8e59%29.html

[xi] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11213-009-9129-9

[xii] https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/an-audit-of-a-unesco-world-heritage-site–the-royal-mile-edinburgh%28ad37dfac-0adc-4138-a401-2c4b31e29173%29.html

[xiii] https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/an-audit-of-a-unesco-world-heritage-site–the-royal-mile-edinburgh-a-preliminary-search-for-authenticity-one-year-later%28d357f288-910a-45ad-ad16-e8cc1652a7a7%29.html

[xiv] https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/an-audit-of-a-unesco-world-heritage-site–the-royal-mile-edinburgh-a-preliminary-search-for-authenticity(894b4963-cf2b-4da1-a888-a0d26017f0fd).html

[xv] https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/portal/files/4739148/12_04.pdf

[xvi] https://newarchitectures.com/c201303/

[xvii] https://newarchitectures.com/2013/03/15/harwood_02/

[xviii] https://www.visitbritain.org/inbound-research-insights

[xix] https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284408214